Matthew Asia: Measuring Intangibles for Growth Companies

Portfolio Managers Taizo Ishida and Michael Oh, CFA, explore the growth drivers for Asia's new economy sectors, including how to measure and assign potential future value of intangible assets.

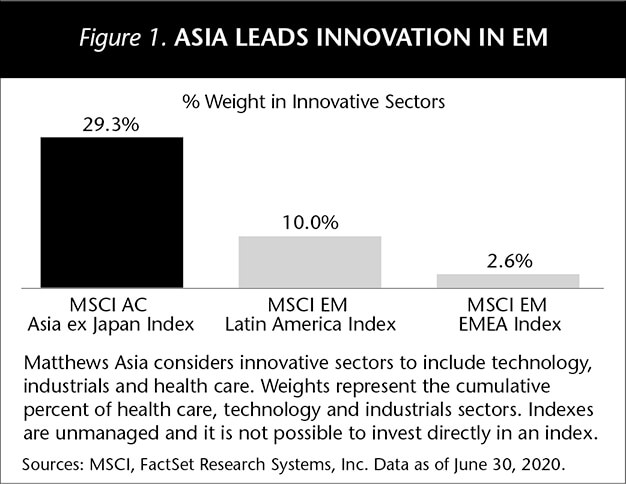

In the recent market rebound, sectors such as health care, communication services, software and online education have generated strong performance, with price-to-earnings multiples for innovative companies in Asia rising. Among fast-growing, innovative companies, intellectual property, network and data may be key drivers of future cash flows. A natural question on investors' minds: “Can growth companies continue their upward trajectories? Or will growth companies see a reversion to the mean?” Portfolio managers Taizo Ishida and Michael Oh, CFA, remain optimistic about the long-term growth potential of innovative companies. In this issue of Asia Insight, we explore the growth drivers for Asia's new economy sectors, including how to measure and assign potential future value of intangible assets.

Growth stocks enjoyed a strong rally the first half of 2020. What's driving gains?

Michael Oh: Returns for growth stocks were indeed strong in the first half. However, if you look closer, you will see a bifurcated market. Companies and sectors that investors perceive as having the potential to come out stronger on the other side of the pandemic have generated much larger gains. Therefore, we need look under the hood and find out what is driving that growth for individual companies. Often, these growth drivers fall into the category of intangible, or nonphysical, assets.

For an e-commerce company, the size and demographics of its user base might be its most meaningful intangible asset. For a biotech company, a patent for a blockbuster drug in a large market such as China might be most important. For an internet search engine, the strength of its algorithms and its position of dominance within local markets might prevail. Each of these falls into the category of intangibles. For high-growth companies, we are most interested in how these intangible assets can help companies grow quickly, while building a competitive moat. As growth investors, we assign a potential future value to these intangibles over time for our portfolio companies.

Many of these innovative companies are running asset-light businesses with the potential for achieving rapid scale at low marginal costs. Valuations matter, but traditional P/E metrics may only tell part of the story. For example, if a company has the potential to double its market cap in the next five years, then its present valuation may be entirely reasonable, even if its stock price has recently appreciated. As always, we believe stock selection and time horizon are key for long-term investors.

What criteria do you use to assign future value to intangible assets?

Taizo Ishida: For measuring intangibles, I tend to start with five key categories. These include the strength of a company's management team and the depth of its product pipeline. I also like to look at the size of a company's comparable industry peers, as well as the size of a company's customer base. Finally, I consider the future potential value of a company's intellectual property. None of these appears on a company's balance sheet. A company that derives its growth potential from these types of intangibles might appear expensive on paper, while still providing the potential for strong returns on a three to five year view.

For a sector like communication services, intangibles are often the primary driver of growth. How do you approach valuation metrics for this sector?

Michael: When we look at a measure like price-to-book, innovative companies often do not have much in the way of hard assets. For a growing video-sharing platform company, for example, we might define their primary asset as having a hundred million users. These users do not show up on a company's balance sheet, but they are potentially worth billions in future revenue for the company. Optically some of these stock prices look expensive if you are using traditional asset valuation metrics. Notably, platform companies can often grow their businesses with low marginal costs. Consider YouTube as an example. Once you set up a platform and attract users, the incremental cost for new users coming online is minimal. Once you have achieved scale, your profitability goes up substantially. This scalability is one of the reasons that platform companies tend to have higher stock price multiples than say those with hard assets such as oil or heavy industrials.

When I value these type of companies, I assign a certain value per user, which can vary a lot from company to company depending on the service it offers. YouTube is an advertising model, while Netflix is a subscription model. So each of these companies have different dollar values assigned to their user base. We see a similar dynamic for Asian platform companies as well. Online platforms can take the form of search engines, e-commerce and entertainment sharing or streaming. We work out the future expected earnings and cash flow for these companies based on the number of users they attract. These companies have a profit structure that is quite different from industries that are asset heavy. For communication services companies, we do not expect these valuations to necessarily reflect or revert to the averages of other industries.

What other sectors are you following most closely these days?

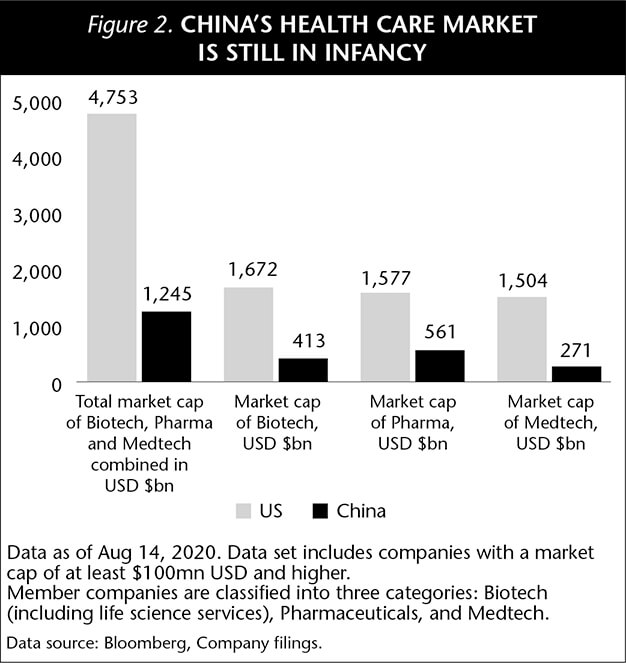

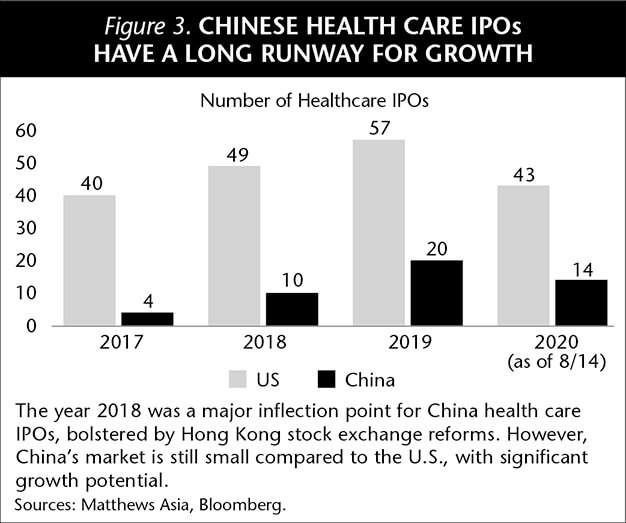

Taizo: Health care is a sector where I believe many global investors are underinvested. The opportunity in Asia—and particularly China—is enormous. For health care companies to generate cash flow from their intellectual property, you need a large addressable market. China's population is roughly four times larger than the U.S., providing a vast market of health care consumers. Yet, the market cap of many Chinese health care companies is really in its infancy when compared to the U.S.

Michael: I believe China may grow into a much larger health care market, which is why it has garnered so much attention these days for growth investors. If you are able to develop an innovative drug that can cure cancer in China for the Chinese patient, your potential value creation is substantial. We could see a cluster of innovative, blockbuster drugs coming out of China in the near future. Some of the drugs also have the potential to be marketed globally. As I mentioned earlier, being a growth investor for me means looking for companies that can at least double in market cap over five years. China's health care market is one of the obvious growth markets that we believe can achieve that.

How is the need for increased productivity driving innovation in Asia?

Michael: As wages go up across Asia, it becomes more expensive to hire employees. Software and automation are two sectors growing rapidly as labor costs rise. The reason we did not see a vibrant software industry arising in Asia earlier is that labor has historically been cheaper than software. Rather than buying desktop software for accounting, for example, you could just hire an extra person in the past. That is no longer the case in Asia. We typically see that inflection point around incomes equivalent to U.S. $8,000-10,000 a year. Therefore, it certainly makes sense for many Asian companies to now buy software rather than hiring extra people. There is an added benefit for companies because your data will be safer with computing systems rather than human systems. Your corporate infrastructure is more stable if you use software. Once you buy software and store your data locally or in the cloud, it stays with you, while labor may move around.

It is the same trend for automation. Ten years ago, it did not make sense for factories to buy machines. You could hire more people. Now, wage increases mean it is no longer cost-efficient to hire more people. The breakeven point for buying automation equipment is often two to three years, compared to earlier times when it took five years to break even. It suddenly makes sense for companies to automate processes using robotics. Entrepreneurs are becoming more sophisticated in Asia, where productivity matters more. If you buy software or employ robots that can do the work of five people now with only two people, that is a better way to go for companies. Automation also minimizes human errors and provides better quality control.

Human capital is also a type of intangible asset. Why start with company management when evaluating a company's talent?

Taizo: The vision of a company's senior executives provides the roadmap for a company's growth. The role of management is to guide a company to its destination. Accordingly, the background of a company's CEO or founder is important. We want to understand the credentials and experience of the key players in the C-Suite. Consider the examples of the biotech and biopharma industries, where the background of executives is very transparent. We know exactly who the executives are, where they went to school and where they worked before. It can be a very small world, even among companies with global operations. We cross check references for senior management and get a handle on the quality of that management. We also want to get to know a company's chief science officer, chief medical officer and/or director of medical research. In addition, the CFO can play a pivotal role in early-stage growth companies. CFOs for young companies need entrepreneurial spirit and drive to go out and find the money to grow the business. When attending industry conferences, we might conduct meetings with up to 10 different pre-IPO companies at a single event. Ultimately, we might participate in only one or two of those IPOs, so we can be very selective about the management teams of the companies we invest in. Management has to be top tier.

Michael: With Asian markets growing so quickly, company management teams really need to be at the top of their game. There is always new competition, as other entrepreneurs enter the fray. From this vantage point, the landscape in Asia looks very different from the U.S. Consider for a moment the U.S. tech giants. Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Alphabet (parent company of Google) appear hard to dislodge. However, these U.S. companies are generally competing for a fixed customer base in a low-growth economy. Turning to Asia, we see a very different picture. Scale and the ability to gain a dominant market share also matter, but the competitive landscape is still evolving. New competitors and disruptors are constantly arising, which makes a strong case for active management. Moreover, Asia's economies are typically growing much faster than the U.S., so the overall size of the opportunity set as measured by customer base and addressable market is still growing in Asia. Growth companies need strong management to steer their ascent.

How do you manage the risks of investing in early-stage growth companies in Asia?

Taizo: For early-stage growth companies, there is no silver bullet for eliminating risk, so we tend to keep position sizes small. In addition, we get to know the management teams of our portfolio companies really well. That helps us interpret the news flow related to individual companies and sort out the noise from information that is valuable.

Michael: In terms of risk management, we want to know how well a company is meeting its milestones and what its future potential market cap may be. We are constantly in dialogue with the management teams. During the pandemic, we visit with companies virtually via video conferences. The Asian market is still growing and evolving. By attending conferences and meeting with companies one-on-one, we strive to keep up with the ever-changing competitive landscape in Asia. We also have team members on the ground in China and Hong Kong to help us keep our fingers on the pulse of markets. In our view, changing dynamics are not necessarily a risk but rather an opportunity. Markets that are constantly changing are great for bottom-up stock pickers. We embrace change because we track the changes and trends in real time. In highly dynamic markets, bottom-up fundamental research is key.

Important information

As of June 30, 2020, Matthews Asia portfolios held no positions in Facebook, Alphabet, Amazon or Netflix.

The views and information discussed in this report are as of the date of publication, are subject to change and may not reflect current views. The views expressed represent an assessment of market conditions at a specific point in time, are opinions only and should not be relied upon as investment advice regarding a particular investment or markets in general. Such information does not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell specific securities or investment vehicles. Investment involves risk. Investing in international and emerging markets may involve additional risks, such as social and political instability, market illiquidity, exchange-rate fluctuations, a high level of volatility and limited regulation. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The information contained herein has been derived from sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of compilation, but no representation or warranty (express or implied) is made as to the accuracy or completeness of any of this information. Matthews Asia and its affiliates do not accept any liability for losses either direct or consequential caused by the use of this information.